Philosophy

Lovers!

Click Here

Who, if Anyone, Deserves our Admiration?

Would Joan of Arc Make your List of Admirable People?

Of the love or hatred God has for the English, I know

nothing, but I do know that they will all be thrown out of France, except

those who die there.

Joan of Arc

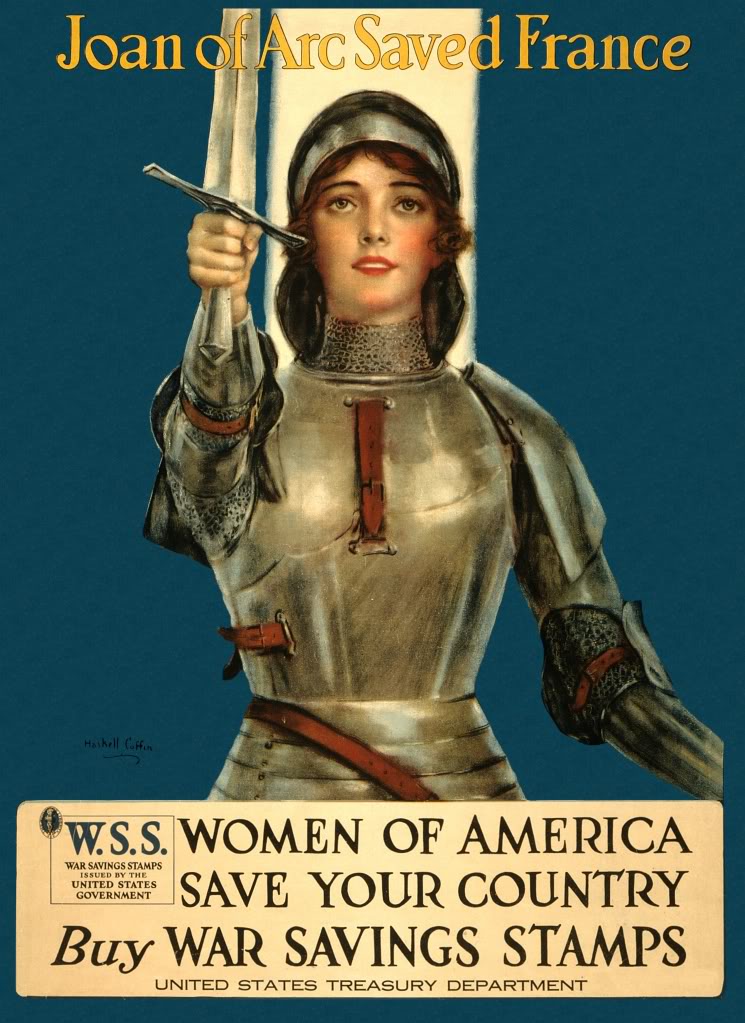

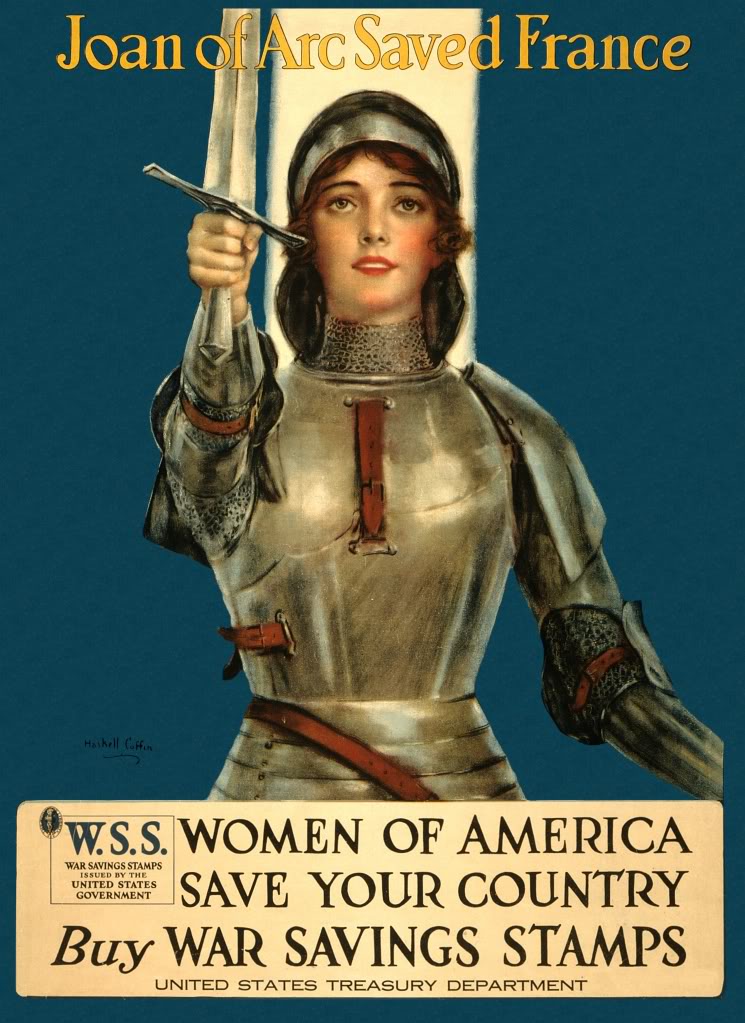

[The patriotic poster on the left was commissioned

by the United States Treasury Department at the time of the First World

War. (Cynics have not failed to note that Joan saved France from

America’s ally in WWI, the English.) More than a few men have

fallen in love with a picture, and between the idealized generic beauty of

her face and her form fitting

armour Haskell Coffin’s heroine

must have stolen the heart of many a young lad. But those who know her

story, like Mark Twain, love her

beyond any personal magnetism or physical allure she may have possessed.

[The patriotic poster on the left was commissioned

by the United States Treasury Department at the time of the First World

War. (Cynics have not failed to note that Joan saved France from

America’s ally in WWI, the English.) More than a few men have

fallen in love with a picture, and between the idealized generic beauty of

her face and her form fitting

armour Haskell Coffin’s heroine

must have stolen the heart of many a young lad. But those who know her

story, like Mark Twain, love her

beyond any personal magnetism or physical allure she may have possessed.

In the photograph on the

right we see one saint portraying another. St Thérèse of Lisieux (1873–1897) was

another famous admirer, even

writing poems and a play about

her—though it should be remembered that Thérèse was a saint and

not a poet, and that poems often lose something in translation.

If you watched all forty-odd films about Joan of

Arc you would never suspect that we know more about her than any other

medieval figure, more about her than just about anyone else until modern

times. (Except with respect to the notions of its director the 1999 film,

The Messenger, is exceptionally unhistorical.) And this wealth of

information, combined with her brief but extraordinary career, has made

her the third most studied and celebrated

figure in Western culture after

Jesus and Napoleon. As we acquaint ourselves with the facts and the

stock image of Joan fades away—by her mere presence on the

battlefield an illiterate peasant girl, shrouded in myth, spurs otherwise

incompetent soldiers on to victory—our admiration is apt

to be tinged at first with envy. At sixteen Joan spun wool and tended

sheep, a pious girl who had never held a sword in her

hand or probably even seen an Englishman. At seventeen she commanded the military forces

of a nation: and she never lost a battle. One of those battles, the lifting

of the Siege of Orleans, is found in Sir Edward Shepherd

Creasy’s famous book, The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the

World. After ninety-two years of engaging in dynastic and civil war

the English

were on the brink of achieving their goal: a dual monarchy. It took

Joan just thirteen months to undo the victories of Poitiers, Crécy and

Agincourt. The

war continued on for another 22 years, but from the

moment Joan arrived on the scene the English cause was doomed.

It’s no wonder they thought she was a witch, a line they took

for over 300 years. Being a witch, they insisted that she was ugly too.

Yet the popular

reappraisal of Joan began, not in France, but in

England. Napoleon jumped on the bandwagon in 1803 and she’s

been invoked by all and sundry ever since.

hand or probably even seen an Englishman. At seventeen she commanded the military forces

of a nation: and she never lost a battle. One of those battles, the lifting

of the Siege of Orleans, is found in Sir Edward Shepherd

Creasy’s famous book, The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the

World. After ninety-two years of engaging in dynastic and civil war

the English

were on the brink of achieving their goal: a dual monarchy. It took

Joan just thirteen months to undo the victories of Poitiers, Crécy and

Agincourt. The

war continued on for another 22 years, but from the

moment Joan arrived on the scene the English cause was doomed.

It’s no wonder they thought she was a witch, a line they took

for over 300 years. Being a witch, they insisted that she was ugly too.

Yet the popular

reappraisal of Joan began, not in France, but in

England. Napoleon jumped on the bandwagon in 1803 and she’s

been invoked by all and sundry ever since.

It should not be imagined that Joan was a mascot, a

merely inspirational presence in the background of battle. On May 7,

1429, she took an arrow between her neck and shoulder during the assault

on the fortified gateway called Les Tourelles. On June 11, during the

battle of Jargeau, a stone projectile struck her helmet, knocking her off a

scaling ladder. On September 8, during the assault on Paris, the bolt from

a crossbow went through her thigh. (There are two schools of thought

about these wounds: either they were much less severe than one would

expect—the bolt from a crossbow was 9 inches long with a 3/4 inch

diameter head of hardened steel while, according to Jean Dunois’

testimony, the arrow, shot from above, penetrated six inches—or

Joan enjoyed God’s providential care.) Despite the military

timidity, political indecision, and frequent opposition of

others—she had many heated exchanges with Dunois in the war

councils—her tactics and strategy invariably produced results.

Many observers, but especially her comrades in the field, testified to her

horsemanship, her skill with sword and lance (a weapon that was effectively

used for the last time by British calvary

against retreating Boers in 1899), her stamina, and, not least,

her uncanny sense of where to place artillery. In the Rouen Trials she

touchingly but naively remarked that she had “never killed

any one.”

It is not generally known that Joan’s

military genius was matched by her skillful defense—she had no

advocate—before a court determined to “have her

yet,” as Cauchon put it. Her presence of mind, subtle replies, and

flawless memory must have driven them

crazy. The trial lasted more than

three grueling months while they wore her down with hardship and threats

of torture. After

trying every trick in the book the trained theologians and

hand-picked prosecutors eventually had to resort to deception. Her

biggest headache had always been how to avoid being seduced by her

comrades or raped by the enemy. Rape was a weapon of war then as it is

now, and although her close comrades professed that there was something

about her that discouraged thoughts of seduction she had many enemies

who had no such qualms. Hence

the wearing of men’s clothing. It was the only chink in her

armour, and eventually they found it. Her story is beyond improbable,

beyond romantic, beyond tragic. If it wasn’t for the fact that we

have complete records of

the trial and the rehabilitation trial 24 years later—discovered in old

archives in the nineteenth century and convergent with everything else

that was known about her—she would be beyond belief.]

We declare that you are fallen again into your former

errors and under the sentence of excommunication which you originally

incurred we decree that you are a relapsed heretic; and by this sentence

which we deliver in writing and pronounce from this tribunal, we

denounce you as a rotten member, which, so that you shall not infect the

other members of Christ, must be cast out of the unity of the Church, cut

off from her body, and given over to the secular power: we cast you off,

separate and abandon you, praying this same secular power on this side of

death and the mutilation of your limbs, to moderate its judgment towards

you, and if true signs of repentance appear in you to permit the sacrament

of penance to be administered to you.

(from the sentence publicly read to Joan before she was burnt at the stake)

In the course of an interview Fr. Benedict Groeschel

told investigative reporter and author of The Miracle Detective,

Randall

Sullivan: “And Joan of Arc, there’s a girl. She

said she spoke to the saints, when what she really saw were statues. But

they spoke to her. Was she crazy? I don’t know. I do know that

she stopped the

longest war in European history. Winston Churchill, no less, said of

Joan, ‘Joan was a being so uplifted from the ordinary run of mankind that

she finds no equal in a thousand years.’ Freud, on the other hand, called her

a schizophrenic. Who’s right? You decide. Was she both mad

and blessed? It’s entirely possible, my friend. Entirely

possible.”

[Nobody could accuse Mark Twain of being well-disposed

towards Christianity or of being on particularly friendly terms

with the deity. Au contraire! Nevertheless, as with so many others, he

fell under Joan’s spell. George Bernard Shaw claimed that he was

infatuated by her—perhaps there’s something about a woman in

armour—but then, as Bernard Levin remarked, Joan was ‘the only woman who ever

managed to wipe the smirk from Shaw’s face.’ In point of fact, the fictionalized

book that Twain wrote about her, Personal Recollections of Joan of

Arc, was solidly researched and much more reliable than

Shaw’s great

play. If the critics were unimpressed and the

public suspected a joke, the book being so out of character, Twain

was unperturbed. On his 73rd birthday, when all his major books

were far behind and he could judge without prejudice, he gave his final

verdict: ‘I like the Joan of Arc best of all my books; & it is

the best; I know it perfectly well. And besides, it furnished me seven

times the pleasure afforded me by any of the others: 12 years of

preparation & a year of writing. The others needed no preparation, & got

none.’ The following passage is from the end of

an essay on Joan

that Twain wrote for Harper’s Magazine in 1904.]

She was deeply religious, and believed that she had

daily speech with angels; that she saw them face to face, and that they

counseled her, comforted and heartened her, and brought commands to

her direct from God. She had a childlike faith in the heavenly origin of

her apparitions and her Voices, and not any threat of any form of death

was able to frighten it out of her loyal heart. She was a beautiful and

simple and lovable character. In the records of the Trials this comes out

in clear and shining detail. She was gentle and winning and affectionate,

she loved her home and friends and her village life; she was miserable in

the presence of pain and suffering; she was full of compassion: on the

field of her most splendid victory she forgot her triumphs to hold in her

lap the head of a dying enemy and comfort his passing spirit with pitying

words; in an age when it was common to slaughter prisoners she stood

dauntless between hers and harm, and saved them alive; she was

forgiving, generous, unselfish, magnanimous; she was pure from all spot

or stain of baseness. And

always she was a girl; and dear and worshipful,

as is meet for that estate: when she fell wounded, the first time, she was

frightened, and cried when she saw her blood gushing from her breast;

but she was Joan of Arc! and when presently she found that her generals

were sounding the retreat, she staggered to her feet and led the assault

again and took that place by storm.

There

is no blemish in that rounded and beautiful character.

How strange it is!—that almost invariably the

artist remembers only one detail—one minor and meaningless

detail of the personality of Joan of Arc: to wit, that she was a peasant

girl—and forgets all the rest; and so he paints her as a strapping

middle-aged fishwoman, with costume to match, and in her face the

spirituality of a ham. He is slave to his one idea, and forgets to observe

that the supremely great souls are never lodged in gross bodies. No

brawn, no muscle, could endure the work that their bodies must do; they

do their miracles by the spirit, which has fifty times the strength and

staying power of brawn and muscle. The Napoleons are little, not big;

and they work twenty hours in the twenty-four, and come up fresh, while

the big soldiers with the little hearts faint around them with fatigue. We

know what Joan of Arc was like without asking—merely by what

she did. The artist

should paint her spirit—then he could not fail to

paint her body aright. She would rise before us then, a vision to win us,

not repel: a lithe young slender figure, instinct with “the unbought grace

of youth,” dear and bonny and lovable, the face beautiful, and

transfigured with the light of that lustrous intellect and the fires of that

unquenchable spirit.

Taking into account, as I have suggested before, all

the circumstances—her origin, youth, sex, illiteracy, early

environment, and the obstructing conditions under which she exploited

her high gifts and made her conquests in the field and before the courts

that tried her for her life,—she is easily and by far the most

extraordinary person the human race has ever produced.

A perfect woman, nobly plann’d,

To warn, to comfort, and command;

And yet a spirit still, and bright

With something of an angel light.

William Wordsworth

Yet Joan, when I came to think of her, had in her all

that was true either in Tolstoy or Nietzsche, all that was even tolerable in

either of them. I thought of all that is noble in Tolstoy, the pleasure in

plain things, especially in plain pity, the actualities of the earth, the

reverence for the poor, the dignity of the bowed back. Joan of Arc had all

that and with this great addition, that she endured poverty as well as

admiring it; whereas Tolstoy is only a typical aristocrat trying to find out

its secret. And then I thought of all that was brave and proud and pathetic

in Nietzsche, and his mutiny against the emptiness and timidity of our

time. I thought of his cry for the ecstatic equilibrium of danger, his

hunger for the rush of great horses, his cry to arms. Well, Joan of Arc had

all that, and again with this difference, that she did not praise fighting, but

fought. We know that she was not afraid of an army, while

Nietzsche, for all we know, was afraid of a cow. Tolstoy only praised the

peasant; she was the peasant. Nietzsche only praised the warrior; she was

the warrior. She beat them both at their own antagonistic ideals; she was

more gentle than the one, more violent than the other. Yet she was a

perfectly practical person who did something, while they are wild

speculators who do nothing.

G. K. Chesterton

Jeanne’s mission was on the surface warlike,

but it really had the effect of ending a century of war, and her love and

charity were so broad, that they could only be matched by Him who

prayed for His murderers.

Arthur Conan Doyle

More

Thoughts about Joan of Arc

Consider this unique and imposing distinction. Since

the writing of human history began, Joan of Arc is the only person, of

either sex, who has ever held supreme command of the military forces of

a nation at the age of seventeen.

Louis Kossuth (19th Century journalist, politician, Hungarian nationalist)

As I wrote she guided my hand, and the words came tumbling

out at such a speed that my pen rushed across the paper and I could barely

write fast enough to put them down.... I do

not profess to understand [her].

George Bernard Shaw

The history of this woman brings us time and again to

tears.

Jules Michelet (19th Century French Historian)

There now appeared upon the ravaged scene an Angel

of Deliverance, the noblest patriot of France, the most splendid of her

heroes, the most beloved of her saints, the most inspiring of all her

memories, the peasant Maid, the ever-shining, ever-glorious Joan of

Arc.

Winston Churchill

Whatever thing men call great, look for it in Joan of

Arc, and there you will find it.

Mark Twain

To download the MS Word (2002) version of this file

click HERE.

To download the WordPerfect (8) version of this file

click HERE.

For more topics in this format

click HERE.

[The patriotic poster on the left was commissioned

by the United States Treasury Department at the time of the First World

War. (Cynics have not failed to note that Joan saved France from

America’s ally in WWI, the English.) More than a few men have

fallen in love with a picture, and between the idealized generic beauty of

her face and her form fitting

armour Haskell Coffin’s heroine

must have stolen the heart of many a young lad. But those who know her

story, like Mark Twain, love her

beyond any personal magnetism or physical allure she may have possessed.

[The patriotic poster on the left was commissioned

by the United States Treasury Department at the time of the First World

War. (Cynics have not failed to note that Joan saved France from

America’s ally in WWI, the English.) More than a few men have

fallen in love with a picture, and between the idealized generic beauty of

her face and her form fitting

armour Haskell Coffin’s heroine

must have stolen the heart of many a young lad. But those who know her

story, like Mark Twain, love her

beyond any personal magnetism or physical allure she may have possessed. hand or probably even seen an Englishman. At seventeen she commanded the military forces

of a nation: and she never lost a battle. One of those battles, the lifting

of

hand or probably even seen an Englishman. At seventeen she commanded the military forces

of a nation: and she never lost a battle. One of those battles, the lifting

of